ATO governance needs reform: IPA-Deakin SME Research Centre

The IPA-Deakin SME Research Centre has examined the shortcomings of the ATO’s governance model and proposed a Tax...

READ MORE

The ATO recently released Draft Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2021/D2 in relation to the allocation of profits for professional firms, to apply from 1 July 2021.

The mischief it is trying to address relates to the owners of a professional firm being taxed on an “artificially low” share of the business’ profits. Lawyers, engineers, architects, doctors, financial planners and accountants are amongst the likely suitors being targeted over how they manage their taxation affairs.

It is a contentious argument as to whether this is discriminative behaviour on behalf of the ATO. Perhaps in some sense it is, as it is specifically targeted, and looked at another way, it provides some level of certainty that firms are swimming between the flags and will not be subject to review if they can show a low-risk rating. The draft PCG is designed to give taxpayers confidence that if their circumstances have a low-risk rating, then the ATO “will generally not allocate compliance resources to test the relevant tax outcomes”.

PCGs in general are statements that the ATO makes on how they will go about doing their primary role of administering taxation laws. In this case, the issue is whether the ATO will have an issue with the allocation of your professional firm’s profits, particularly if it involves taxpayers who redirect their income to an associated entity where it has the effect of altering the principal practitioner’s tax liability.

There are no new laws in operation, other than the existing anti-avoidance rules (Part IVA), which fundamentally apply equally to all taxpayers. Despite Part IVA applying to all taxpayers, this PCG effectively amounts to the ATO singling out professional firms with a tailored compliance approach on how such firms allocate their profits. No other group has been singled out for special treatment on how they split their income. A mum and dad partnership that splits their income to pay less tax does not receive this special attention.

Provided your business’ profits are not personal exertion income and are allocated as permitted by your business structure (company, trust etc), your professional firm’s profits are no different to those earned in any other industry (such as retailing).

Further, no anti-avoidance laws will have been breached in relation to the mere profit allocation itself.

In the absence of Part IVA factors, is the goal to intimidate professional firms into conservative tax outcomes, one asks? Perhaps this is the intended outcome as Part IVA requires the Commissioner to undertake a determination which is administratively burdensome for the ATO to undertake on a case-by-case basis. The PCG effectively puts the onus on the taxpayer to self-assess, and in doing so, to provide this information to the ATO in response to an information request, which could lead to a review. I could not imagine many firms would be willing to engage in litigation and air their taxation arrangements in the public domain in the process of defending an amended assessment. For small firms there is a significant power differential at play here, as the vast majority of affected businesses are in no position to want to take on the ATO.

History first

Tax planning dates back to the dawn of time and has continued unabated ever since. The concept of trying to split income to pay less tax remains the lure that taxpayers seek to achieve legitimately if the circumstances allow for such tax planning. It all started in 2015 when the ATO issued guidelines regarding the allocation of profits within professional firms. The guidelines were suddenly withdrawn in December 2017, mainly as a result of being misinterpreted in relation to arrangements that went beyond their scope.

The ATO was identifying scenarios where groups of professionals were restructuring themselves to access the suspended guidelines. The suspended guidelines were intended for existing structures. On 1 March 2021 the ATO issued replacement guidance by way of draft PCG 2021/D2 after much consultation. For those who were accustomed to the suspended guidelines, the framework for assessing risk in the Draft PCG is much more complex and can move entities up the risk scale, so the goal posts have shifted. Thankfully this has been recognised as part of the transitional arrangements (see page 74) allowing firms to continue to apply the suspended guidelines until June 2023.

Under the previous Suspended Guidelines, a return of profit of 50 per cent in the hands of the individual professional practitioners (IPP) would have been considered low risk on its own (i.e. without needing to meet any other risk assessment factor). Similarly, an effective tax rate of 30 per cent for income received from the firm by the IPP and associated entities would have been considered low risk on its own.

However, under the Draft PCG, the same circumstances would receive a score of 9 and a high-risk rating. A 1 per cent difference for either measure (i.e. 51 per cent of income return in the hands of IPP or an effective tax rate of 31 per cent) would still yield a score of 8, and a moderate risk rating. Some relatively minor adjustments to the manner in which risk is measured (i.e. the numbers) has resulted in a significant risk rating change.

What’s it all about

The PCG is relevant only for professional firms where the profits are not “personal exertion” income. That is, it won’t apply to, for example, a sole trader (even where operating through an entity), as the profits must be allocated to that individual in any case subject to the personal services income regime.

So, we’re generally concerning ourselves with professional firms that have professional staff in addition to the IPP. The ATO’s concern is over the owners of a professional firm being taxed on an “artificially low” share of the business’s profits by channeling a portion to an associated entity or entities such as a trust, company or family member with the aim of paying a lower marginal tax rate than if the income were taxed in the hands of IPP.

Allocation of your business’ profits – gateway

A taxpayer must pass through two gateways before being able to rely on the draft PCG.

Gateway 1 considers whether the arrangement, and the way it operates, are commercially driven. The arrangement must also be appropriately documented and there must be evidence that the stated commercial purpose was achieved as a result of the arrangement. There must also be a genuine commercial basis for the way in which profits are distributed within the group, especially in the form of remuneration paid. Relevant considerations are whether:

the IPP actually receives an amount of the profits or income which reflects a reward for their personal efforts or skill;

Gateway 2 requires that the arrangement must not contain potentially high-risk features, such as:

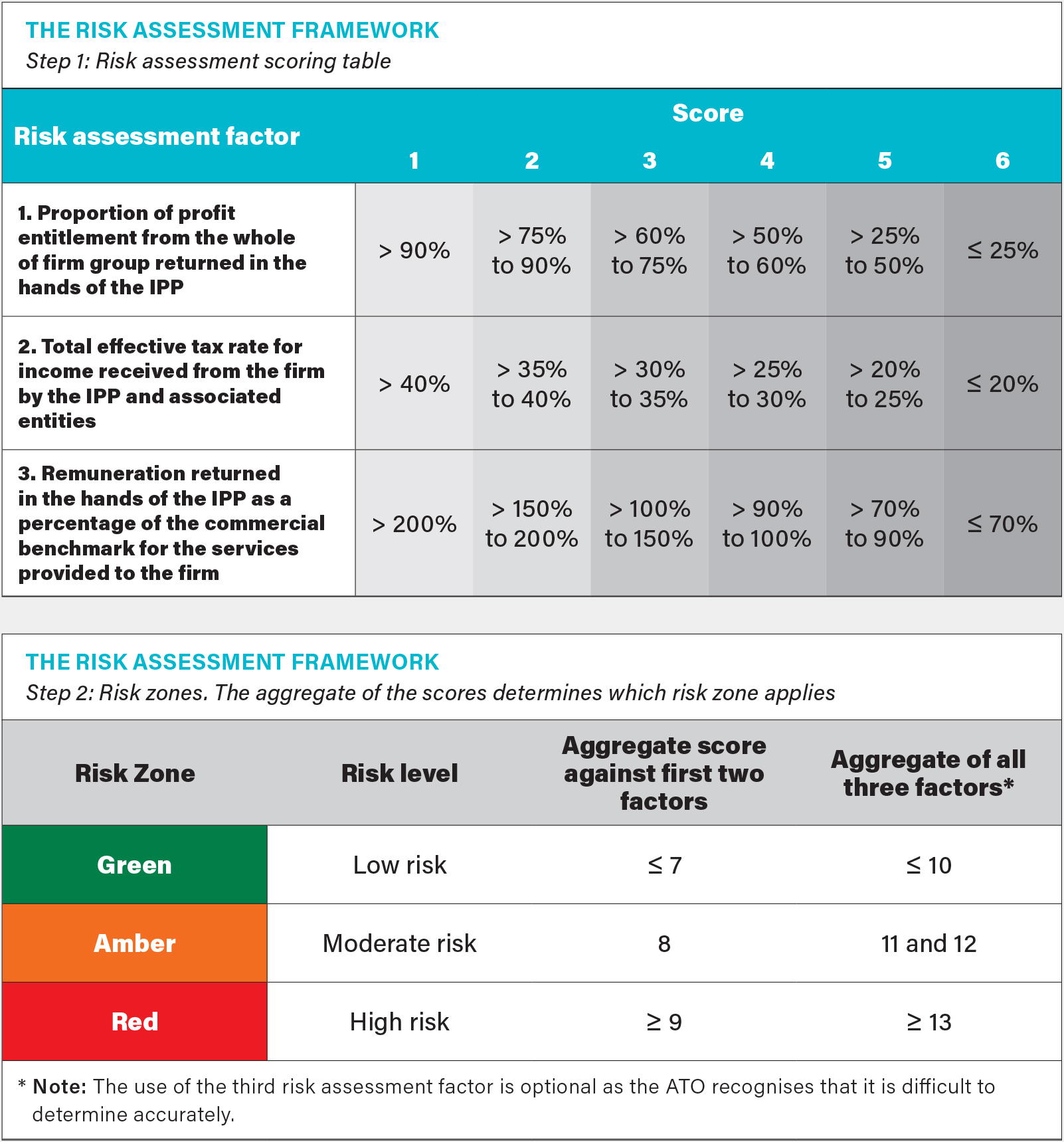

If a taxpayer satisfies Gateways 1 and 2, the draft PCG provides a “risk assessment scoring table” that assigns a score depending on:

The first two risk assessment factors may be used, instead of all three, where it is impractical to accurately determine an appropriate commercial remuneration against which to benchmark.

Those risk scores are added up to place a taxpayer within a low, medium or high-risk level zone (green, amber or red). As less and less is allocated to the owners, and more to related parties, this sends you to the amber zone, and then the red zone. If you’re in the green zone, in the absence of exceptional circumstances, the ATO will be unlikely to commit compliance resources your way.

If you’re in the amber or red zones, expect further analysis of your arrangements. Priority focus will be given to those in the red zone, perhaps even proceeding directly to an audit.

One would expect that once the PCG is finalised that the ATO is likely to use its formal powers for information gathering to obtain information on how entities have self-assessed their risk rating.

General anti-avoidance rules still apply

The draft PCG does not constitute a “safe harbour” or relieve taxpayers of their legal obligation to self-assess their compliance with relevant tax laws. The general anti-avoidance provisions in Part IVA of the ITAA 1936 will continue to apply to schemes designed to ensure the IPP is not appropriately rewarded for the services they provide to the business, or receives a reward substantially less than the value of those services despite the existence of a business structure. The draft PCG is designed to give taxpayers confidence that if their circumstances have a low-risk rating, the ATO “will generally not allocate compliance resources to test the relevant tax outcomes”.

The use of companies, trusts and other business structures do not of themselves give rise to avoidance concerns. However, if the use of the structure is to redirect income inappropriately, then Part IVA can apply. When the business involves the provision of services, the ATO will be concerned with arrangements where the compensation received by the individual is artificially low while related entities benefit (or the individual ultimately benefits), and commercial reasons do not justify the arrangement.

Date of effect and transitional arrangements

When finalised, the PCG will apply from 1 July 2021. The ATO says the use and application of the PCG will be reviewed from and during 2022, “any revisions to improve its efficacy will be made on an ‘as necessary’ basis”.

The ATO says it recognises that the publication of the PCG may cause taxpayers to review their existing arrangements. Consequently, some taxpayers may modify their arrangements to prospectively come within the green zone. Para 103 of the draft PCG should be noted:

“103. Taxpayers who entered into arrangements prior to 14 December 2017 are able to continue to rely on the suspended Assessing the risk: allocation of profits within professional firms guidelines (Suspended Guidelines) (published on ato.gov.au in 2015) for the years ending 30 June 2018, 30 June 2019, 30 June 2020 and 30 June 2021, as long as their arrangement complies with those Suspended Guidelines, is commercially-driven, and does not exhibit any of the high-risk features outlined in paragraph 42 of [the draft PCG]. In recognition that certain arrangements considered low risk under the Suspended Guidelines may have a higher risk rating under this Guideline, we are allowing a grace period for those IPPs to take the required steps to modify their arrangements to be lower risk, if they choose. Accordingly, those IPPs may continue to apply the Suspended Guidelines to their arrangements until 30 June 2023.”

If a taxpayer identifies that they are no longer low risk, and they wish to transition their arrangements to a lower risk zone, they can inform the ATO of their intentions at any time. If the taxpayer engages with the ATO in good faith, this engagement will be on a ‘without prejudice’ basis.

The ATO has a dedicated team for the oversight and management of profit allocation arrangement risks. Email: ProfessionalPdts@ato.gov.au

Initial reactions

Our initial reactions include the following:

Small changes in the profit distribution and tax rate can significantly change the compliance risk result and therefore the likelihood of attracting compliance attention from the ATO. The risk rating of an IPP can move from low to high based on a small change in the profit distribution and tax rate amount. The risk assessment scoring table and risk zones indicate that provided IPPs receive a proportion of profit entitlement of greater than 50 per cent (say 50.1 per cent) and a total effective tax rate of greater than 30 per cent (say 30.1 per cent), they would be in the green zone. Only a small amount of change to the proportion of profit can move the risk rating into the red zone. Smaller, less profitable firms may be disadvantaged as a result. IPPs in firms with higher total income will have a reduced risk rating as income returned by the IPP will be subject to higher marginal rates, therefore bringing the total effective tax rate up. Given that risk rating may not equate to the existence of any Part IVA factors, the PCG can therefore lead to unnecessary compliance activity and costs.

The draft PCG contains five examples illustrating how to apply different aspects of the proposed compliance approach and seven case studies. However, the guideline does not contain any examples of the common scenario of professional firms run through a corporate structure. Inclusion of such examples would then ideally need to also address following factors:

We would hope that prior to finalisation of the Draft PCG, examples of this common practice structure are considered, including issues noted above and form part of amended PCG risk assessment guidance.

As noted in the joint submission by the accounting bodies, the Draft PCG is primarily a guide to assess the likelihood of the ATO reviewing the affairs of an IPP and his/her firm with a view to applying the general anti-avoidance provisions in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Part IVA).

However, we observe that the exclusionary “Gateways” and risk assessment framework are not necessarily constructed to align with Part IVA factors. Rather, the Draft PCG uses broad, unadjusted measures as proxies for Part IVA risk. As a result, the risk scores reflect neither the nuance nor specificity required to properly assess the level of risk. Nor does the Draft PCG provide either the ATO or the IPP with assurance that arrangements with high risk scores are, in fact, likely to be those to which Part IVA could be successfully applied.

There is no general principle of taxation law dealing with, or proscribing, the so-called “alienation of income”. That is, in the absence of specific statutory provisions such as the personal services income or general anti-avoidance rules, there is no general principle which brings about the result that the income or profit beneficially derived by a partnership, company or trustee of a trust, that has arisen from the personal exertion or skilled labour of an individual, can be regarded as the profit or income of that individual. It does not matter how involved such an individual may be in the activities from which the income is derived by the entity.

Given this situation, it is likely that professional firms may feel coerced into changing their current arrangements even where the IPP can show that they are remunerated on an arm’s length basis for the services they provide to the firm. Is the goal of the PCG to intimidate professional firms into conservative tax outcomes in the absence of Part IVA factors? Profit or income of a professional firm usually comprise different components — reflecting a mixture of income from the efforts, labour and application of skills of the firm’s IPPs (that is, personal exertion) and income generated by the business structure including intellectual property. The proportion of profits benchmarked in the risk assessment scoring table applies a one-size-fits-all approach which does not take into account the differing profitability of various firms and different types of professions. The profitability of firms can differ greatly between different firms and/or professions depending on their location, the types of clients and the specialties and capabilities of the IPPs and their staff. Some are more reliant on the professional expertise and services provided by the principal IPPs and for others profitability is more dependent on the services and expertise provided by the structure, other IPPs and staff members.

Not many firms would be willing to engage in litigation and disclose their taxation arrangements in the public domain in the process of mounting a defence against a review if litigation is the only way to fight an amended assessment. For small firms there is a significant power differential at play here, as the vast majority of affected businesses are in no position to want to take on the ATO.

The effective tax rate thresholds do not factor in the legislated reductions in corporate and individual tax rates. We believe that this will result in a very large number of IPPs across a broad range of firms being classified as moderate or high risk when their arrangements are highly unlikely to trigger Part IVA. When the original guidance was released in 2015, the corporate tax rate was universally 30 per cent. The reduction in the rate to 25 per cent from 1 July 2021 will result in a score of 5 using risk assessment factor 2, making it much easier to fall in the amber or red zone. This is further exacerbated by the increases in the personal income tax thresholds, which now means that for an individual to have an average tax rate of 30 per cent, they need to have earnings of just over $195,000.

Total effective tax rate

The risk assessment factor for the ‘total effective tax rate’ discriminates against smaller/less profitable firms and part-time IPPs. Some suburban and country firms and part-time IPPs may not attain the more than 30 per cent average tax rate even if receiving a substantial majority of the relevant share of the firm’s ‘profits’.

In summary

Following a period for receiving comments, the draft PCG is expected to be finalised in the coming months, and the ATO will apply it to the 2021–22 year onwards. Based on your existing profit-allocation practices, firms will need to assess which zone you’ll likely land in for 2021–22.

If it’s looking like you’ll land in the amber or red zones, and you’re uncomfortable with the position, you may need to plan for a different profit allocation that will shift you towards the green zone. It’s also unclear how the ATO will review your zone self-assessment, as this is not readily ascertainable from the existing information disclosed so it may need to rely on its information gathering powers to request this information.

It’s early days so we will need to see what changes are made to the PCG after the consultation process has been finalised.